Microbes do not live in isolation, but form complex communities. It is this form of communal living that underpins vital processes for Earth's functioning, including the turnover of organic matter and nutrient cycling.We are interested in understanding how microbial communities assemble and what determines their structure and function.

To this end, we build microbial microcosms where communities obtained from natural habitats assemble in well-defined and easy-to-tune environmental conditions, in combination with phenotyping of community members. We use results from such experiments to generate hypotheses that we can test in real-world settings or using the wealth of publicly available microbiome data.

This approach allows us to connect metabolism and related traits (e.g., growth rate) to relevant community properties, including diversity, composition, and function, and to identify unifying principles for how microbial communities modify and respond to their environment.

Nutrient-mediated interactions and community diversity

Microbes are the most metabolically diverse form of life on the planet. They can use a long list of sources of carbon to sustain their growth, which includes pollutants and plastic components. The availability of carbon sources in nutrient pools, i.e., the number of different substrates, their type, and concentration, determines which species are able to grow, at which rate, and the abundance they can reach. We are interested in understanding how the metabolic network that assembles in a particular community depends on the availability of carbon sources, and what this means for the diversity and structure of such community.

Our work has shown that the number of carbon sources in the environment determines the diversity of bacterial communities in soil microcosms. Current work examines how sugar and organic acid concentrations shape interspecies competition and community structure, with plans to expand studies to phosphorus and nitrogen sources.

Decoding the evolution of anticipation and decision making

Funded by Human Frontier Science Program

In an international collaboration with the McGlynn lab (Japan) and the Grilli research group (Italy), we aim to understand how microbes "learn" and anticipate environmental changes—a crucial ability for their survival.

We investigate diverse microbial species in various environments—from stable to repetitive and random—to determine how much information cells can "remember" based on environmental predictability. We explore factors like genome size and growth rates, and use nanoSIMS enabled single-cell observations to track nutrient uptake and understand individuality within populations.

By combining experimental data with mathematical models and evolutionary experiments, we seek to develop a general understanding of learning mechanisms and their limits across the microbial world.

Ecological drivers of fast and slow growers

A pervasive concept in ecology is the distribution of fast and slow growers. For example, patterns of successions after a disturbance in plants, corals, and other macroorganisms are usually described in terms of fast growers paving the way for slow growers. Grow rate is indeed a key component of life strategies of both macro- and microorganisms, determining their ability to survive and compete in a given environment. We are exploring how environmental variables like temperature and salinity, by predictably affecting growth rates, shape the outcome of species competition and the structure of microbiomes at different spatial and temporal scales. As key environmental variables are altered by climate change, it is crucial to predict how their effects on species traits such as growth rates translate to changes in community patterns.

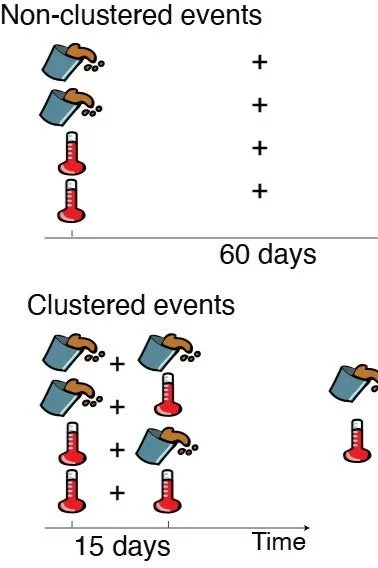

Memory and community response to perturbations

As perturbation regimes are altered by environmental change, it is crucial to understand and possibly predict community dynamics. However, how communities respond to perturbations depends not just on current conditions, but also on previous states and environmental history (see Dal Bello et al. 2017, Rindi et al. 2017, Dal Bello et al. 2019). In other words, communities, but also populations and entire ecosystems, have memory. We are interested in understanding what aspects of “ecological memory”, either biotic – such as the prevalent mode of metabolic interactions between community members – and/or abiotic – for example available energy in the environment – are important to predict future community states.